Native Americans of the Huron River Watershed

The Native Americans that settled the Great Lakes Basin 10,000 years ago were largely affiliated with the Algonquin Nation, a people who had been driven by the Iroquois from Canada’s Georgian Bay. These early Native Americans were nomadic hunters and gatherers who pursued mastodons, woolly mammoths and migratory game along the edges of the receding glaciers. Over time, this migratory population came to organize themselves into three major tribal cultures; the Ojibwe (also known as Chippewa), Ottawa, and Potawatomi, forming a loose confederation known as the Three Fires.1 The Ojibwe occupied parts of Canada, Wisconsin and the upper peninsula of Michigan. The Ottawa, to some degree a more nomadic people, occupied the norther third of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula and traveled throughout the Great Lakes area. The Potawatomi occupied the southern region of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula as well as parts of Ohio, Illinois and southern Wisconsin.2 A fourth group of Native Americans, the Wyandot (also known as Wendats or later called HURONS by the French) also settled in southeastern Michigan. Both the Wyandot and the Potawatomi established permanent and semi-permanent villages along the Huron River.1

Potawatomi in Athens, Michigan 1830

Potawatomi in Athens, Michigan 1830The Potawatomi practiced and were highly dependent on community farming. They grew corn, squash and beans as their staple crops. They also used wild plants to spice foods and for medicinal use. For example, sumac berries were boiled for a tea similar to lemonade; raspberries were also boiled for a tea that removed tartar from teeth and the leaves were mixed into a paste and applied to sores; cattail roots and stems were eaten, flowers used for diaper lining and leaves for weaving. From the many lakes and streams in the area, the Potawatomi added fish, beaver, turtles, snails and crayfish to their diet. Their fishing gear included bone fishhooks, notched pebble sinkers and nets woven from wild flax, milkweed, swamp ash, and the inner bark of the basswood tree.2

The Huron River Watershed was of prime importance to the Potawatomi tribe. By traveling upriver from Lake Erie to a tributary known as Portage Creek, it was possible to get within less than a mile of a tributary of the Grand River, which flows into Lake Michigan. The Potawatomi could take a large canoe all of the way across southern Michigan with only one portage (land crossing) of approximately a mile.3

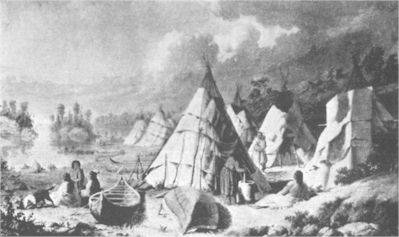

Wyandot (Huron) encampment along the Islands of Lake Huron. Paul Kane.1845

Wyandot (Huron) encampment along the Islands of Lake Huron. Paul Kane.1845It appears some Wyandot (Huron) Indians fished, hunted and grew crops in the area around Little Portage Lake. They built birch bark canoes like those used by the Algonquin, but took their farming practices from the Iroquois. Clear division of labor between the sexes required women to be in charge of farming. The men did the hunting and fishing. The Wyandot also participated in the beaver fur trade paddling their canoes through the lakes in search of animals.4

By the 1720s, European settlement within the watershed began in earnest. The area was considered highly desirable. The river was described as “a very rapidly flowing stream with a sand bottom” that made it ideal for the construction of dams to create power for saw and grain mills. This lead to the clearing of land and development of agriculture in the basin. However both the Potawatomi and Wyandot peoples suffered devastating losses of life from diseases brought into the region by settlers. In 1752, most of the Potawatomi died from smallpox. In 1787, the Wyandot people were struck by this illness. When whooping cough arrived in 1813, the few remaining groups were again devastated. The Wyandot who survived this moved to southern Ontario. By 1866, the Potawatomi of the Huron, now numbering less than 100 individuals, moved to Athens, south of Battle Creek. After this, except for isolated members, no North American Indians were left in the watershed.3

References:

- Huron River Watershed Council: Human History. http://www.hrwc.org/the-watershed/features/human-history/

- Clinton Watershed Council. Native Americans of the Clinton River Watershed http://www.crwc.org/watershed/native-american-history/

- Hay-Chmielsewski EM et al. Huron River Assessment. State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources. April 1995.pages 16-17. http://michiganlakes.msue.msu.edu/uploads/files/Chmielewski%20et%20al.%201995.pdf

- Jernigan M. History of Little Portage Lake, Michigan. USA Today Travel Tips. October 16, 2013. http://traveltips.usatoday.com/history-little-portage-lake-michigan-101613.html